NETWORKED WONDERS: THE INTERNET AS ANTAGONIST AND ALLY IN ZARDULU’S “TRICONIS AETERNIS: RITES AND MYSTERIES”

By Tim Schneider

The Realness

Although Zardulu is often (with her approval) described as a creator of “viral hoaxes,” this designation is both a valuable and a dangerous portal through which to enter her practice. The reason is that thinking about hoaxes, whether viral or analog, intuitively tempts us to imagine a bright line separating truth and fiction.

Yet a key tenet of the artist’s years-long project is that such clear answers are scarcer than they have ever been before. And this realization opens the door to her far larger, more consequential, and more enduring investigations into the necessity of myth and wonder in an age overloaded by information.

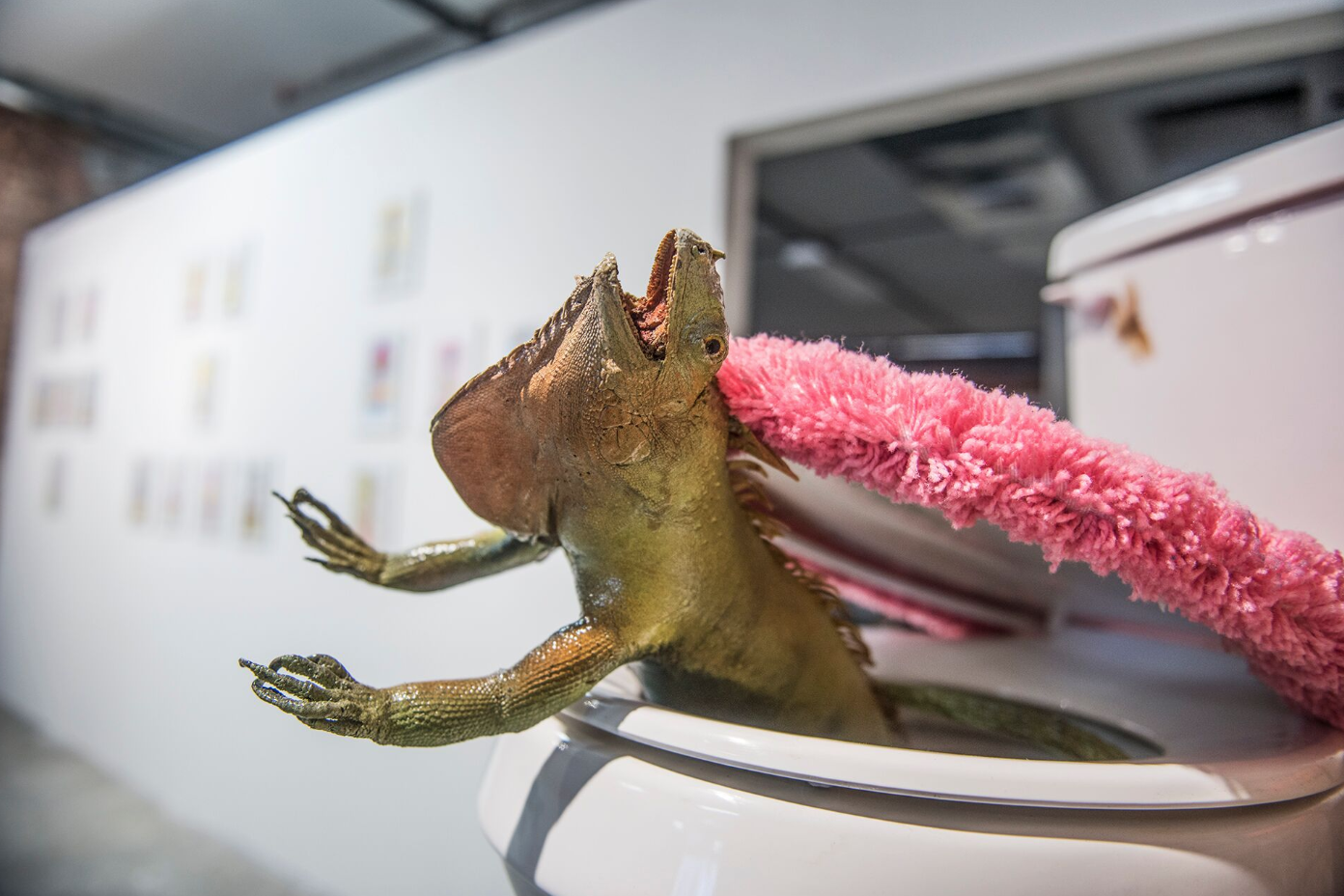

Detail of ‘Usurpation of Ouranos’ from Zardulu the Mythmaker Unique (2017) Mixed-media, taxidermy, viral media coverage.

As an introduction to these dynamics, consider The Usurpation of Ouranos, the Zardulu work that ricocheted across old and new media alike during the week of Art Basel Miami Beach in 2017. In a handheld amateur video first aired by Telemundo, a bewildered Latinx family is thrown into low-level pandemonium by a large, rambunctious iguana that seems to have crawled up the sewage pipes into their guest bathroom’s toilet.

Although we see no violence on video, the young man at the center of the footage claims that the iguana emerged and bit him on… let’s say “his most sensitive appendage” after he sat down to relieve himself. The commotion soon draws some of his relatives into the scene, and amid the resulting frenzy, the iguana escapes the toilet, the bathroom, and finally, the house.

The video’s spread was accompanied (and in part, driven) by heated debates about its veracity. After Zardulu claimed the piece as her own via a feature in The New York Times, though, many more viewers than before settled on the notion that the video was “fake.”(1)

Telemundo “Familia de Hialeah dice iguana entró por toilet” November 30th, 2017

The video’s spread was accompanied (and in part, driven) by heated debates about its veracity. After Zardulu claimed the piece as her own via a feature in The New York Times, though, many more viewers than before settled on the notion that the video was “fake.”

But what does “fake” mean in this context, exactly?

But what does “fake” mean in this context, exactly?

The prevailing answer was that it meant an iguana didn’t actually crawl into the family’s toilet of its own free will, and it didn’t actually nip anyone’s dick. Also, the videographer didn’t actually stumble into their role spontaneously. All of these components were either setups by Zardulu (the first and third) or outright fabrications (the second).

But on the other hand: The iguana was actually a live iguana, actually inside an actual toilet in an actual home, and it actually struck minor terror into the actual unsuspecting family members present. All of the above were confirmed when the young man, a local drag performer known as Gio Profera, later admitted he was the only resident of the house in on the prank. His relatives’ panicked reactions on camera certainly seem to back up his statements.

Furthermore, the iguana’s escape was actually caught on video, and that actual video aired on an actual multinational news broadcast as an actual story for actual viewers, before it actually went viral as an actual thing millions of people shared and debated online—in no small part because, as the Times pointed out, there is an actual phenomenon of iguanas emerging from Floridian toilets. (2)

In that sense, the best answer to the question “real or fake?” is probably the simplest one: Yes.

Crucially, this same call and response now applies to the lives each of us lives online. Who we are, what we do, and what we believe the rest of the world to be—none of these are strictly matters of fact anymore. They are all endlessly fungible variables, determined in the moment by what we choose to conjure and consume through the sorcery of the internet.

Who we are, what we do, and what we believe the rest of the world to be—none of these are strictly matters of fact anymore.

And the sooner we make peace with this answer, the sooner we can look past the crumbling firewall separating fact and fiction and onto Zardulu’s grander goal in The Usurpation of Ouranos. There, as in all the other works included in her inaugural gallery exhibition, “Triconis Aeternis: Rites and Mysteries,” the title clarifies the artist’s intent to vault past contemporary hoaxing toward contemporary mythmaking. And to understand why this practice matters in the present, we first need to understand the context of the past.

The Death of Myth

I used the term “contemporary mythmaking” above because western civilization has been single-mindedly aiding and abetting the world in pushing its old myths into oblivion since at least the late 17th century. In Europe, that era saw the dawn of the Enlightenment, AKA the Age of Reason: a roughly 130-year period defined by the reshaping of society around the beliefs that the world was knowable, that rationality should rule, and that there was no higher calling than to question authority.

By the early 19th century, many of the myths of Europe and their descendants in the still-young United States were ash. The prevailing attitude in these societies largely equated human advancement with the reign of cold logic

In practice, questioning authority also meant questioning tradition. And tradition, in so many cases, meant the mythologies handed down by our ancestors through cultural epochs less inclined toward scientific inquiry. By definition, then, the Age of Reason turned a flamethrower on myths, and Enlightenment thinkers judged their success on how much scorched earth they left in their wake.

By the early 19th century, many of the myths of Europe and their descendants in the still-young United States were ash. The prevailing attitude in these societies largely equated human advancement with the reign of cold logic—a perspective perhaps best prefigured in Sir Francis Bacon’s 1605 tract The Advancement of Learning, where the philosopher defined wonder as “broken knowledge,” or an error that can (and should) be corrected.

While it would be naïve to pretend there was no pushback to this trend—for instance, myths were vigorously championed by the Romanticists near the end of the 18th century and Carl Jung in the 20th century—Bacon’s view has, for the most part, only become more dominant in the time since. After all, what earlier signpost is there on a child’s road to maturity than their discovery that Santa Claus or the tooth fairy is a benevolent hoax? Just as important, science and technology have generally surged along the same trajectory in eastern cultures, too, with globalization increasingly ensuring that societies around the world saw (and see) progress in rationalistic terms.

Spread from 'Triconis Aeternis: Rites and Mysteries

However, even after the Enlightenment’s end around 1815, one fortress of myth survived and, in fact, thrived for another 150 years of western history: the Abrahamic religions, or Judaism, Christianity, and Islam. As Zardulu wrote to me during this essay’s construction, “One person’s theology is another person’s mythology.”

But at least here in the US, even that final bastion of resistance has been breached. Theology in America has now been in decline for nearly 50 years, with nonbelievers already outnumbering members of all but two Abrahamic sects as of my writing (3). And if the current trajectories continue, Americans with no religious affiliation are estimated to overtake those last two holdouts—Catholics and Protestants—by 2030 (4).

What caused such a steep and sudden increase in skepticism of the strongest remaining myths in America? Although a complex web of factors is undoubtedly involved, one appears to dominate all the others: the advent of the internet. According to Scott Galloway, professor at NYU’s Stern School of Business, “The strongest signal for disbelief in religion is internet usage, accounting for more than a quarter of America’s drift from religion. (5)”

This destructive relationship hinges partly on the internet’s elimination of much of the existential uncertainty that used to drive so many of us to organized religions (and apart from them, non-Abrahamic myths). We can now get an answer to just about anything, anywhere, on demand, as long as we have a Wi-Fi signal and one of the tiny handheld computers that we now misleadingly refer to simply as phones.

What caused such a steep and sudden increase in skepticism of the strongest remaining myths in America?

Although a complex web of factors is undoubtedly involved, one appears to dominate all the others: the advent of the internet.

In one sense, this is wondrous. In another, it may be wonder’s apocalypse: the ultimate fix for what remains of our “broken knowledge.”

The grand irony is that a technology promising infinite answers and unprecedented connectivity has dramatically shrunken the scope of contemporary life in the developed world. From cultural consumption to personal relationships to even the most basic chores, our experiences are increasingly mediated by our screens. In this sense, the death of myth is tied to both the explosive availability of facts and the simultaneous retreat of direct engagement.

And yet, in matters small and large, it’s undeniable that fabrications, misconceptions, and conspiracies frequently overpower verifiable truths in the digital age. Reality’s nascent fluidity has been harnessed by profiteers, ideological zealots, and people like you and me who just want to, say, construct the most appealing online version of ourselves to impress an Instagram crush.

As Zardulu once explained, “In the digital age, we can be anything we want. We can be a stoic businessperson on our LinkedIn page and be smashing a beer can on our foreheads on our Facebook page. It’s the age of the avatar.” (6) And her practice hinges on the realization that mythology is both the source of this affliction and its antidote.

Fighting Fire with Fire

Installation view 'Triconis Aeternis:Rites and Mysteries' at TRANSFER #ONCANAL presented by Wallplay from October 4th – November 8th 2018 inside 321 Canal Street, New York, NY.

Upon entering “Triconis Aeternis: Rites and Mysteries,” viewers are greeted by a pair of gargantuan monitors looping a cacophonous montage of online media. This endless force-feed contains coverage of every viral hoax the artist has claimed and commemorated deeper inside the exhibition space.

The introductory screens are much more than a curatorial flourish. They are an active reminder of both the essence of Zardulu’s work and, just as important, what she is reacting against. While discussing The Founding and Manifesto of Zardulism, the artist’s online statement of purpose, she explained to me in a Twitter message that one of the text’s core arguments is that…

Corporations, marketers, and advertisers have taken over the role of storyteller. They create myths that define our values and worldview, and what I’m doing is essentially using their existing infrastructure to subvert them. A kind of guerrilla media, culture jamming, using my own mythologies.

There is artistic precedent for this tactic. Zardulu has often voiced admiration for the Situationist International (SI), an avant-garde faction active in Europe between 1957 and 1972. The SI sought to disrupt what it saw as an all-encompassing capitalist illusion dictating that life was best lived through the acquisition of products. Its weapon of choice against this pervasive “spectacle,” in SI terminology, was a series of actions dubbed “situations,” each meant to jolt viewers awake to the supremely unnatural lifestyle they’d come to accept as natural under a perverse set of priorities.

Networked communication is vital to this practice. While the Situationists’ reach was limited by old media, Zardulu’s arms are infinite thanks to digitization.

Situations involved SI operatives hijacking establishment settings and media (particularly live TV) to create surrealist interventions in daily life. Perhaps the most infamous of these saw SI members upend a televised Easter Sunday mass at Paris’s Notre-Dame cathedral by helping member Michel Mourre, dressed as a Franciscan monk, deliver a heretical sermon from the rostrum during a moment of silence.

However, what evolves Zardulu’s works past SI situations is her specific reliance on the internet. Networked communication is vital to this practice. While the Situationists’ reach was limited by old media, Zardulu’s arms are infinite thanks to digitization. As the manifesto proposes, “For the first time in history, myths can be created in mere moments.” Her benevolent viral hoaxes become instantly shareable and endlessly transmittable, growing stronger with each new audience member as they dart around the globe.

Crucially, Zardulu’s prospects are maximized by our cross-cultural hunger for myths—a hunger thrust into extremes by the advent of the information age. Although she didn’t mean it in quite this way, the dynamic calls to mind Joan Didion’s famous assertion, “We tell ourselves stories in order to live.” Yes, the internet deluged us with data, knowledge, and convenience, but we need something more primal, more emotional, more dramatic to be fulfilled.

In short, storytelling has been more powerful than facts for millennia. The current political landscape proves this is still the case in 2018—not despite the rise of reason and technology but because of it. For good or for ill, the internet made the world flat, and Zardulu sees that it can be used for re-inflation, too.

But what happens when those myths move offline in the age of the avatar?

Mausoleum of Myths(?)

'Ketois Troias' (2018) in the foreground, Unique (2018) Mixed-media, taxidermy, viral media coverage. Also pictured: 'The Watchmen of Lo' (2016), 'Hegesistraus’ Sacrifice' (2017) and 'The Usurpation of Ouranos' (2017)

The core of “Triconis Aeternis: Rites and Mysteries” represents a fork in Zardulu’s practice. Atop classic white pedestals, seven static sculptures dot the gallery. Each sculpture features at least one taxidermied animal used to either create or commemorate one of the artist’s viral hoaxes. (An eighth sculpture may or may not sit atop a pedestal in one back corner. As of my writing, it remained covered by a shroud.)

To flesh out its context, every sculpture is accompanied by accessories of some kind. Usually, these take the form of fake terrain and faux plants attached to the same base as the taxidermy, creating something similar to the environmental dioramas you would see in a natural history museum. One exception, however, happens to be The Usurpation of Ouranos, which takes the form of a taxidermied iguana protruding from a full-sized toilet with the same fuzzy pink seat topper as the one seen in Gio Profera’s family’s guest bathroom.

Zardulu the Mythmaker installation view 'Hegesistraus’ Sacrifice' (2016) in the foreground, 'The Watchmen of Lo' (2015) in the background

Seeing these viral stories frozen in place in the physical world—presented as literal carcasses, however well preserved and manicured—fundamentally changes our experience of them. In contrast to the works in their viral form, the tangible sculptures radiate finality.

Zardulu claimed authorship of the memes, or contemporary myths, behind some of these works well before the exhibition’s opening. Apart from The Usurpation of Ouranos, she has also previously taken credit in the press for The Watchmen of Lo, featuring a three-eyed catfish allegedly fished out of Brooklyn’s notoriously filthy Gowanus Canal; Ketos Troias, a dual-finned serpent whose eviscerated “corpse” was captured on video on a Georgia beach in March 2018; and three others on view in the show.

The only fresh revelation of Zardulism is Leto and the Lycians, a bikini constructed from skinned frogs. Worn at the time by the (invented?) Louisiana bayou vixen Fabiana Lefleur, the piece gained internet fame via coverage in the Huffington Post and Reddit in spring 2018. The mannequin modeling the work in the exhibition also harbors a reference to another, smaller online sensation: an ant caught on camera in the act of “stealing” a diamond on an anonymous desktop.

Seeing these viral stories frozen in place in the physical world—presented as literal carcasses, however well preserved and manicured—fundamentally changes our experience of them. In contrast to the works in their viral form, the tangible sculptures radiate finality. Here are the core facts of these formerly mysterious events, displayed under floodlights, helpless against interrogation. The exhibition essentially builds a mausoleum of myths.

Yet deadening these once-lively sources of online fascination is both valuable and, according to the artist, intentional. Presented as tangible objects—the truth of the memes’ execution—the sculptures make up a kind of Unnatural History Museum: a deliberately backward-looking collection that proves the stories to be more meaningful to us than the facts, the same way stuffed saber-toothed tigers can only ever be faint shadows of the primal forces they were while prowling the earth.

“Triconis Aeternis” offers the cold logic of how Zardulu engineered the surreal images (moving or still) that so many of us debated via digital and analog interactions over the past several years. We can be amused by the sculptures but not invigorated by them, because the wonder and community are gone. What was once mysterious, shared, and expansive has been reduced to a finite set of clear-cut realities any individual visitor can process on their own.

Presented as tangible objects—the truth of the memes’ execution—the sculptures make up a kind of Unnatural History Museum: a deliberately backward-looking collection that proves the stories to be more meaningful to us than the facts.

Or at least, they can if they choose to take Zardulu at her word—a decision fraught with the same tensions as deciding whether the viral hoaxes were “real” or “fake” in the first place. The shrouded work nods to the notion that the artist still has many other contemporary myths worming their way through the internet, possibly never to be claimed.

She will continue adding to her viral canon, too, spurred on, she says, by the dreams depicted in the works on paper that bracket the sculptures inside the gallery space. Marrying classical tarot imagery with Zardulu’s personal nocturnal visions, these gouaches allude to an unending, universal cycle. It begins with the Jungian notion of the collective unconscious—a vocabulary of archetypes shared by all humans across time and cultures—proceeds through the artist’s hand to painting, sculpture, and action, then comes to life online when a single, mysterious post gets sucked into the thirsty hive mind of the internet.

Detail view ‘Shores of the Acheron’ (2016) Mixed-media, taxidermy, viral media coverage.

According to Jung and others, this is a similar path traveled by the original myths exiled by Enlightenment thinking and technology. The theory explains why one culture’s myths so often parallel the myths of other peoples in other places, all told centuries before any worldly interaction between these civilizations occurred. So even as Zardulu titles her works after ancient Greek myths, the referenced narratives echo around the globe.

What was once mysterious, shared, and expansive has been reduced to a finite set of clear-cut realities any individual visitor can process on their own.

For instance, Ketos Troias takes its name from Hercules’s battle with a sea monster of the same moniker, which swallowed him whole and forced the hero to gash his way free with a fishhook. But this is essentially the same story as the one Jews, Christians, and Muslims tell about the prophet Jonah being swallowed by the whale (or “big fish”), only to emerge again unharmed. It is also the reason that Zardulu staged the piece near Darien, Georgia, a region that has long told tales of the Altamaha-ha, a serpent rumored to inhabit the nearby Altamaha River dating back to when the Lower Muskogee Creek tribe held dominion there.

These threads show Zardulu’s project to be both ancient and contemporary, far-reaching and personal, always-ending and never-ending. As our increasingly screen-mediated existence narrows further, bringing more waves of cold certainty and self-serving fabrications to dash old wonders against the rocks, we will need new wonders as desperately as ever. In this era, what more vital role could an artist play than creating those benevolent wonders—and what more “real” artwork could we ask for than what they produce?

Catalog Essay by Tim Schneider

Request a print catalog by writing to director@transfergallery.com

View Online ExhibitionFootnotes

1. Andy Newman, “From the Artist Behind the Selfie Rat, Meet the Toilet Iguana,” The New York Times, December 10, 2017, https://www.nytimes.com/2017/12/10/arts/zardulu-rat-toilet-iguana-video.html

2. Ibid.

3. Allen Downey, “The US Is Retreating from Religion,” Scientific American, October 20, 2017, https://blogs.scientificamerican.com/observations/the-u-s-is-retreating-from-religion/

4. Ibid.

5. Scott Galloway, The Four: The Hidden DNA of Amazon, Apple, Facebook, and Google (New York: Portfolio/Penguin, 2017).

6. Constance Grady, “Where Pizza Rat, Fake News, and Art Collide, There’s a Wizard Named Zardulu,” Vox, May 31, 2017, https://www.vox.com/culture/2017/4/24/14912316/zardulu-viral-videos-mythmaking-surrealism-pedro-lasch

7. Zardulu the Mythmaker, The Founding and Manifesto of Zardulism.

8. Joan Didion, The White Album (New York: Open Road, 1979).

9. Andy Newman, “The Artist Behind the Three-Eyed Fish and Selfie Rat, and Other Hoaxes,” The New York Times, March 28, 2016, https://www.nytimes.com/2016/03/29/nyregion/zardulu-artist-selfie-rat-pizza-rat-viral-internet-hoaxes.html; Lauren Messman, “This Washed-Up Sea Creature Was the Work of Viral Hoaxer Zardulu,” Vice, September 18, 2018 https://www.vice.com/en_us/article/59apnx/this-washed-up-sea-creature-was-the-work-of-viral-hoaxer-zardulu

10. David Moye, “Louisiana Woman Creates Frog Bikini (and It’s Ribbiting),” Huffington Post, April 12, 2018, https://www.huffingtonpost.com/entry/fabiana-lefleur-frog-bikini_us_5acf71d8e4b0d4931c8af7ea.

11. “Altamaha – Serpent of the Altamaha River in Georgia,” Legends of America, https://www.legendsofamerica.com/ga-altamahaha/